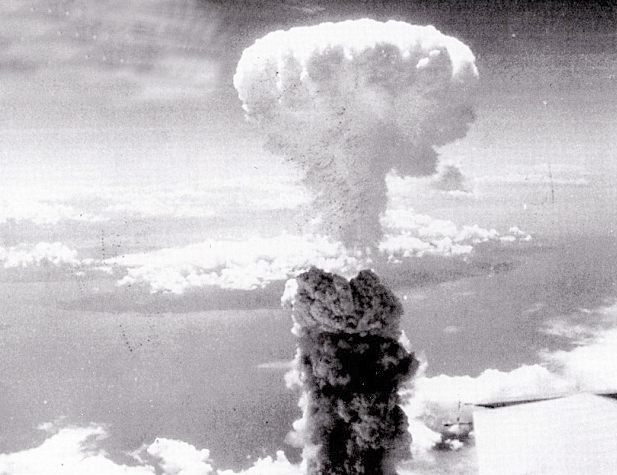

On August 6th, 1945 at 8:15 in morning the United States dropped a nuclear bomb out of the bottom of a B-29 Super Fortress flying over Hiroshima. 44 seconds later, it detonated 2,000 feet above the city, instantly killing 70,000 of the city’s 350,000 inhabitants. 115 days into his term, President Truman authorized the beginning of the age of nuclear weapons. On his 118th day he confirmed it by authorizing a second nuclear attack on Nagasaki that killed 55,000 of its 240,000 inhabitants. Five days later, the Empire of Japan surrendered, ending the war that started 57 months earlier with the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By August,1945 the United States stood alone in the world with the power to win any war it chose through use of nuclear weapons.

We would not be alone for long.

By 1949, Russia would join America as a nuclear power. The United Kingdom followed in 1952. France joined by 1960.

By 1953 with the development of the Hydrogen bomb, the capability of nuclear weapons began to transition from the capacity to end a war to the capacity to end the world. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of nuclear weapons wrote in an article in Foreign Affairs that year about the U.S. and the Soviets being on a path where they would soon be “two scorpions in a bottle each capable of killing the other, only at the risk of his own life.”

In a letter to his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles from September of 1953, President Eisenhower showed how earnestly he measured our options. “We would be forced to consider whether or not our duty to future generations did not require us to initiate war at the most propitious moment we could designate.” Few realize how close we came to a pre-emptive strike on the Soviet Union. Much to his credit, Eisenhower wrestled the initiative of nuclear weapons from those who would wield them for tactical utility by making their impact a global societal prerogative. Only something the President could do. And we soon settled on a policy of massive response as Dulles would put it, to “retain the mighty land power of the Communist world.”

By the Kennedy administration, the Soviet Union and the United States reached the plateau of mutually assured destruction. We both possessed the quantity and delivery methods of nuclear weapons at a scale to ensure that one could destroy the other even if they managed to shoot second. The optimistic outcome of such a predicament was the reduction of the risk of atomic  war in service to self-preservation. In 1962 the Cuban missile crisis would test that theory.

war in service to self-preservation. In 1962 the Cuban missile crisis would test that theory.

The world was on edge while the U.S. and the Soviet Union stood at the brink of nuclear war over the discovery of the tactical placement of nuclear missiles 90 miles from the U.S. in Cuba. As President Kennedy measured his options for response, he contacted Iowa corn seed salesmen Roswell Garst.

Three years earlier Russian Premier Vladimir Khrushchev visited Garst to discuss corn seeds. More specifically, the he was interested in increasing the output of Russia’s crop to better feed his people. Kennedy learned from Garst the only material thing that anyone has to know about nuclear war amongst the backdrop of mutually assured destruction. He knew that the other guy wasn’t interested in the extinction of his people. That was the key to Kennedy opening up a back channel of communication that ultimately ended the crisis without war.

Three years earlier Russian Premier Vladimir Khrushchev visited Garst to discuss corn seeds. More specifically, the he was interested in increasing the output of Russia’s crop to better feed his people. Kennedy learned from Garst the only material thing that anyone has to know about nuclear war amongst the backdrop of mutually assured destruction. He knew that the other guy wasn’t interested in the extinction of his people. That was the key to Kennedy opening up a back channel of communication that ultimately ended the crisis without war.

According to the CIA fact book, eight countries, the U.S., Russia, U.K., France, China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have successfully detonated a nuclear bomb. Israel is rumored to be able to, but has not been confirmed. In 2011 the Atomic Energy Agency released a publication citing “credible” information that Iran may be developing a nuclear weapon. That’s where we are today, 70 years after we started.

This September, Congress will vote to approve or reject a deal that would halt nuclear weapons development in Iran in return for the lifting of long-standing economic sanctions. Critics of the deal state that it will enable Iran to develop weapons earlier than the present policy would enable. Supporters believe it will not. That is a gross over simplification of the details but it’s a fair summation of the principles of the argument. There’s something horribly wrong with the debate though. And it’s politics. When asked about Iran and nuclear weapons, 99 year old Bernard Lewis, the uncontested greatest living authority on 20th century Middle Eastern history and culture, gave dire warning. When it comes to mutually assured destruction, he stated, “for them (Iran), it’s not a deterrent. It’s an inducement.” Which in corn seed salesmen terms means, the other guy might be ok with extinction. Which means that Iran and Israel are quickly approaching territory with nuclear weapons that we haven’t seen in 60 years.

And we’re addressing this issue the same way we’re debating taxes or healthcare or gun control; right down party lines. And that’s a problem.

With such enormity of consequence, I ask not a specific outcome for the vote. To be clear, it’s a complicated issue. But it’s not one beyond the grasp of the legislative body of the most powerful democracy the world has ever seen. It’s going to take a more evolved approach than politics though; one more suitable to the task. One adopted by former New York Times Jerusalem Bureau Chief Thomas Friedman. You see, Tom Friedman won the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 for his coverage of the war in Lebanon. He won it again in 1988 for his reporting on Israel. He won it again in 2002 for reporting on the impact of international terrorism. It’s safe to say that Tom knows more about Middle Eastern affairs than any ten members of congress. About the time that our elected officials were downloading their opinions from their partisan benefactors, Tom Freidman said this. “Personally, I want more time to study the deal, hear from the nonpartisan experts, listen to what the Iranian leaders tell their own people and hear what credible alternative strategies the critics have to offer.” This one matters too much, to settle for any less. But right now, less is what we’re getting. Let history remind us, 70 years to the day since it started, what power is at stake here, and what ends we must gain in order to survive.