The American story is one long continuous struggle to expand our sense of self. Our charter identifies our union as an establishment of the people, by the people, for the people. In that we have been universally consistent. The grand internal struggle has been and still is answering one question. Who are the people?

The great civil rights saga of the past 230 years has played itself out in the form of protest, legislation and even war. Nowhere is this more clear than in the evolution of our immigration policy. Few things serve as a more accurate proxy of our collective efforts to include or exclude than how we guard access to our most sacred gift of citizenship. One underlying theme flows through our past though. Exclusion gives way to inclusion, and our country grows in strength and relevance. We’ve long since determined that the eligibility for the honor of being ordained American lies not in one’s specificity of race or national origin. Hundreds of years of painful, sometimes violent, change has beaten back that particular call for nativism into the dark corners of our society. Instead we have but one more hard question to answer. And this question sits at the heart of our 21st century immigration debate. How should one become one of “We the people”?

Understanding that we Americans have varying degrees of comfort with the concept of inclusion, it may be hard for some to accept the theme that exclusion giving way to inclusion is universally positive. Taking a little time to study the language of our legislation and the light it sheds on the horrifying ideologies that motivated it can help with that. Here’s what happened over the first 180 years or so.

The United States Naturalization Law of 1790 granted citizenship to free white persons of “good character.” The emphasis of course being on white. We were less specific about the metrics of good character. We added all people born in America with the 14th Amendment 80 years later after we killed about 600 thousand of each other to solve the question of slavery.

In 1870, we included “aliens of African nativity and persons of African decent” but excluded “all other non-whites” from citizenship. It’s not particularly clear what is included in “all other non-whites” but it was implied that it meant everyone else…in the world.

By the 1890’s we opened the floodgates at Ellis Island and started to realize that we needed a national strategy for immigration. After all, our citizenship laws were pretty basic. White’s and blacks are in. All others are out. There were a lot of other people out there though so we needed to take action. Enter the immigration Act of 1917. The act was specific in barring, “homosexuals, idiots, feeble minded persons, criminals, epeleptics, insane persons, alcoholics, professional beggars (amatuers were fine), all mentally or physically defective, polygamists and anarchists”. And one other group….all Asians. Previously only Chinese were not allowed to immigrate. We let them back in 1943.

By 1921, we shifted to an emergency quota system, which allowed up to 3% of any given national origin, as documented in the 1890 census, to immigrate to the United States. This sounds on the surface to be an equitable approach. Though somehow people of Asian decent still weren’t allowed to be citizens yet. Since most people in America in 1890 were of German, Irish or British decent, from 1921 to 1965, 70% of all immigrants came from those countries. We did make progress though. The Luce-Celler Act let people of Asian decent be real live American citizens in 1946. It also allowed for 100 immigrants a year from each Asian country. Yes….100

Enter the Hart-Celler Act of 1965. This actually, for the most part, is our current policy of record. It focused on skills based Visas and immediate family of American citizens.

Oddly, there’s little mention at all in any of the immigration policies aimed specifically at Latin America. Which is interesting because the term immigration in 2015 is almost entirely about Latinos. Referring to the United States Census Bureau adds to the confusion because Hispanic is actually not a race according to them. It’s an ethnicity. I encourage anyone to read their explanation of the difference and make heads or tails of it.

If you’re confused and amazed and potentially outraged by this collection of facts and timelines, don’t fear, that’s normal. If anything, it strengthens my resolve in the belief that applying high level intellectual thought to the categorization of human beings isn’t a great use of our time.

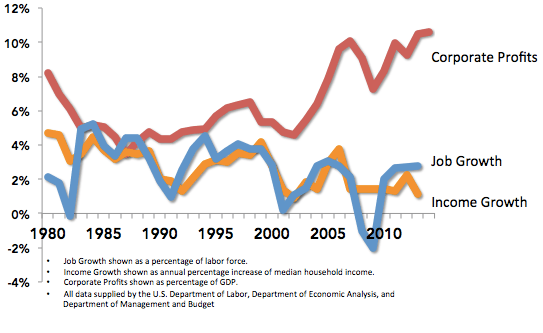

So what does it all really tell us. It tells us that our history on immigration and citizenship is not a straight line. Our preferences and policies bounce from one crisis to another with knee-jerk reaction to whatever hysteria is happening at the time. Without question though, when you read out loud the actual words of exclusion in our policies, it sounds ridiculous. Because it is. Nowhere in our history does it show a period of inclusion followed by horrifying social or economic outcomes as a result. Since we broadened the scope of our immigration allowances, we have seen a massive influx of people from around the world of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. We are not, however, overrun by foreign-born people. By 2013, 13% of people residing in our country were not born here. With the exception of the 30 years following WWII, 13% is entirely aligned with our historic norms. It’s usually been about 12-13%. Certainly since 1965, innovation and economic growth have not been impacted. We have been and are still as relevant, profitable and prosperous as we’ve ever been. So what’s the problem? It relates back to our original question. How does one become one of “We the people”? In this, we actually find two problems. One of them isn’t hard at all, if we’re honest about it. The other is tougher.

The first problem: What do we do with the 12M undocumented immigrants presently living on our country? This is not going to be a popular answer in certain circles but it’s pretty clear if you look at it through a historically contextual lens. Which is what you do when you want to make a good decision. What we do is we find a way to make as many of those who are not here in a legal status, legal residents with the fastest path to citizenship possible. And we do it quickly. They are already here and participating in our economy and our society. 60% of them are located in six states, Texas, California, Arizona, New Jersey, New York and Florida. Which means that for 44 of our 50 states, this is an issue in principle only. This isn’t about skills either. They’re already doing the work that others won’t. The engine of an upwardly mobile society fires best when those at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum are there because they just arrived; not because they’ve been held there by generations of exclusive and divisive policy (see Jim Crow).

I am also not forgetting that this group of people “broke the law”. One of the wonderful bi-products of military service over the past 15 years or so, is that you get to see the world, one destitute wasteland at a time. In doing so you truly appreciate the beacon of hope and progress that is the first world. Having had that experience, I will not begrudge any person who, assuming they’ve broke no other laws, simply does exactly what I would do if I were born into the hopeless poverty that these people come from. When we’re truly honest with ourselves, most people can find a way to accept that. Unless of course they are in the throws of the second issue. Good old fashion fear. That issue will be more difficult to crack.

The fear of foreigners in our country is as old as our country. From the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, all the way up through our modern debate about undocumented residents, it has been present. The level of fear, like the common ebb and flow of modern opinions tends to be related to our reactions to whichever event we’re closest to in our history. To highlight just how different our views can and have swung, check out a comparison of two national party platforms.

Platform 1:

We believe there should be local educational programs which enable those who grew up learning another language such as Spanish to become proficient in English while also maintaining their own language and cultural heritage. Neither Hispanics nor any other American citizens should be barred from education or employment opportunities because English is not their first language.

Platform 2:

To ensure that all students have access to the mainstream of American life, we support the English First approach and oppose divisive programs that limit students’ ability to advance in American society.

Surprisingly, both of these platforms come from the same party; The Republican Party. The first one was what Ronald Reagan ran on in 1980. The second is the one Mitt Romney ran on in 2012. By definition, both highlight the conservative view on the most basic of cultural identity aspects, language. They also show that, even in the conservative circles, our points of view are highly subject to our national mood. And right now, our mood is still very afraid.

We’re 14 years beyond the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and quickly approaching, I hope, the back slope of a fear peak. As we approach the great political debate that will be the 2016 presidential election, how can we have the most effective outcomes relative to immigration? Take the fear out of it. If we don’t we’ll get something that resembles the “birther” debate, which has a special place in my heart. I’ve actually lived in Kenya. Any person who is one generation removed from someone who figured out how to get out of there should be celebrated, not forced to show their birth certificate or called a religion that they’re not. Kenya, by the way, is about 70% Christian. As an independent, nothing turned me off more to the conservative cause during the 2008 presidential election than the layers of stupidity that was the “birther “debate. So when it comes to immigration, let’s not do that. When it comes to immigration, let’s be fearless. Because in war, business and policy, the motivation of fear is an absolute killer. Replace your fear with thoughtfulness and perspective. The history shows it’s the path to prosperity and progress.