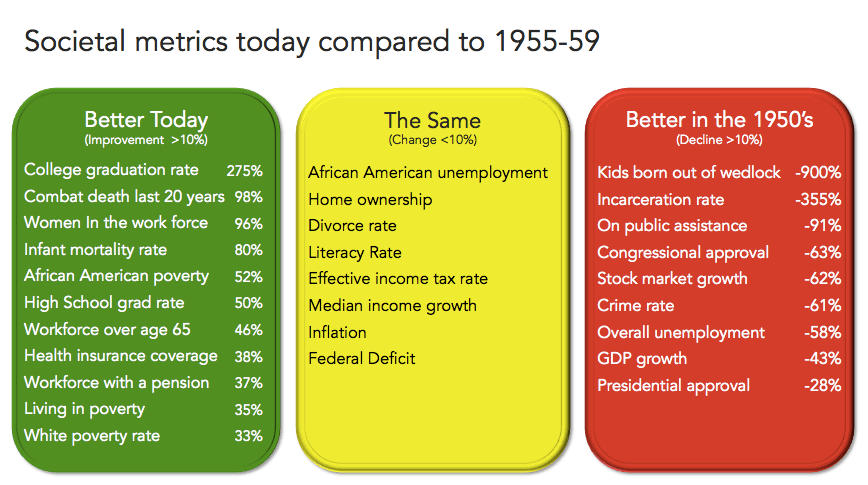

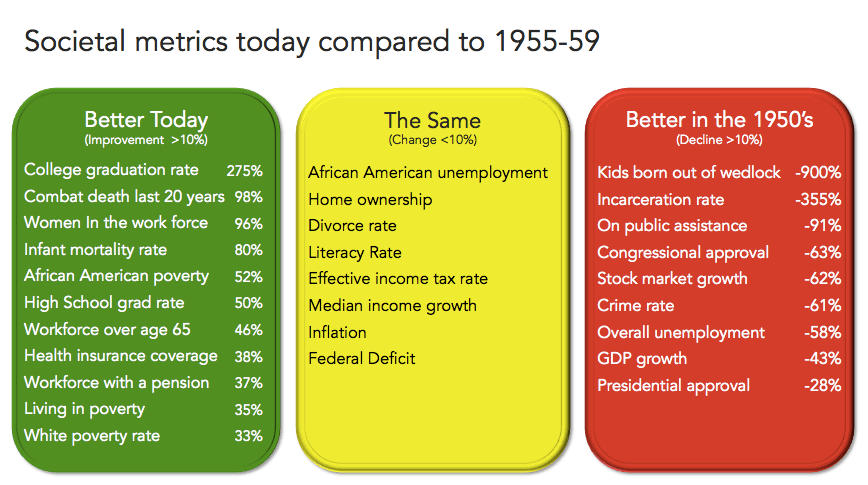

Table-1. Data compiled form the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Labor, U.S. Census Bureau, The Pewe Research Center, The Brookings Institute and Gallup

Table-1. Data compiled form the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Labor, U.S. Census Bureau, The Pewe Research Center, The Brookings Institute and Gallup

You’ve heard it. At some point someone you know has said it. It may have been you. But you’ve heard someone somewhere longing for the better times of the past. A time in America where “traditional” values were embraced by all and we lived in a harmonious utopia, swimming in the perfectly temperate waters of civility that could only come from a simpler life. A time when people treated each other better. Where we were safer and less exposed to the horrors that our modern world bestows upon us. A time before the treacherous “next” generation had infected our stoic wisdom with dangerous thinking, loose morals, and a tragic lack of work ethic. A time where America was great. When today, she is something else. You know the tone. It’s one part nostalgic and one part condescension. It’s a sentiment that’s been around as long as our collective conscience as a species has spanned more than our own immediate horizon. It’s what we do. We long for the past.

For Americans, that time we long for is actually quite specific. It still lives in the distant memories of our older two generations. The “golden age” of America, the 1950’s, is that time that represents the zero, zero grid on the Cartesian graph that is America. It was the post-war origin of our greatness. The Garden of Eden before the apple. But was it really that great? Are we really that worse off today?

Taking a contextual look at the data can help. So we did. We took 28 societal metrics that were clearly measurable during the second half of the 1950’s and today and did a comparison. Our findings, in Chart-1 above, were extremely interesting. Of the 28 items, 11 were measurably better today than in the 1950’s. Eight were about the same, within 10% better or worse. Nine were measurably worse. Of the 28 metrics that can be directly compared, less than 1/3 of them were measurably better in the “golden age”. The data alone isn’t enough to tell the story though. But it certainly gives us a few places to start to look. And it’s important that we do. Because having an informed perspective about “what’s wrong with America” is a responsibility that requires more than whimsy and nostalgia. It requires more than a bumper sticker or a snappy hat. It requires fact in introspection. Here’s what we found:

Family Life

Contrary to popular belief, marriages aren’t falling apart any faster now than they were 60 years ago. The divorce rate is slightly lower today than back then. Which is one of the more surprising metrics. One thing that is happening is that less people are getting married. Which has contributed in some part to what is the largest difference in all the data used in the comparison, children born out of wedlock. In 2014, 42% of all children born in America were born to unmarried parents. This is nine times the rate that they were in the 1950’s. One of the more commonly politicized metrics is the present level of African American children born out of wedlock, which was 74% in 2013. That’s a striking number. There’s more to it than race though. The issue is actually not being driven by any ethnic or culturally specific trend. Since 1965, that rate that African American children are born to unmarried parents has tripled. During the same time, the rate that children are born to unmarried white parents has increased by a factor of ten.

Peeling back the onion a little more, we see that in previous decades from the 70-90’s, the increase in unmarried births was in teenagers, which correlated to the decrease in the “shotgun marriage” practices. More recently though, the increase is in women in their 20’s during the last decade and now women in their 30’s in the present decade. Couple that data point with the fact that less people are getting married, and we see that the traditional American family structure has gone through a radical change over the last sixty years, most specifically because the institution of marriage is in decline. And there’s a very sound argument that it’s not good.

A massive increase in children born to unwed parents is at a minimum, not great. Not from a morality perspective, though for some, that is where most of the energy is spent on this topic. It’s not great because of the outcomes it yields. I’m not a big fan of statistics pointing out how children of single parents have lower graduation rates, higher crime rates and eventually higher unemployment. That data is more correlation than causation because single parent rates have a perfect correlation to socioeconomic levels. There’s an easier way to get to that conclusion though. It’s this. Married parents are less likely to split than unmarried ones. That results in more single parents and reduces the resources a child has for income, care, involvement and an almost unending list of parental requirements by 50%. Which increases the amount of instability in a child’s life.

All this leads you to the hard fact that children born out of wedlock have less consistency and less income during their formative years then those born to two married parents. And from an outcomes perspective, child development experts uniformly agree that consistency is the single most important aspect of a child’s development. Which means that we really were in a much better place from a family perspective 60 years ago than we are today.

So what do we do about it? I don’t really know. As a person who appreciates liberty and limited government involvement in things like my family and personal choices, I’m not a fan of trying to legislate our way to increasing marriage rates. There are many “free market” forces in play here, from workplace opportunity for women to daycare availability to cultural norms that are causing headwinds to the institution of marriage. And one thing that I am certain doesn’t help is limiting who can marry who…in any way. If we’re interested in growing back a family structure, let’s try not painting the institution of marriage in the irrelevant light of exclusion, bigotry and tradition. You might find that the next generation of Americans value it more. And that’s really the goal. More people living within the structure of a family. Anything else, really doesn’t help.

The Workplace

This one isn’t really even close. We have more women and more diversity and more inclusion in the workplace than we did 60 years ago. After decades of shifting from a manufacturing economy to a services and technology one, we’ve managed to maintain wage growth above inflation and delivered work environments safer than at any time in our history. We went through the great recession and that hurts our last decade worth of numbers. Though unemployment over the last ten years was higher, comparing the great recession to the economic boom created by the post war reconstruction environment was a tough compare. We’re back today from an unemployment and wages perspective where we were in a relative sense to where we were in 1959 though. One of the things that jumps out is that we actually had a higher percentage of people working over 65 in the 1950’s than we do today. Which is counter to the notion that no one can afford to retire today. We even have more people receiving a pension today then we did before, though that growth is entirely in the public sector. We have more people living longer after they’ve left the work force independently than any time in the history of our country. This is good. But as we’ll see in the next section, it doesn’t come for free.

Entitlements and Taxation

Almost all of our federal spending increase over the last 60 years has been used to sustain social entitlements. Whether it be social safety net services, retirement income or medical expenses, government growth has been largely focused in this space. This is one I’d actually prefer to explain with a needs and outcomes discussion, instead of a rhetorical rant about the evils of government. Here’s how it goes.

In 1959, there were 177 Million Americans with a median age of 29.7 years old who lived to be 71 years old. Today there are 320 million American with a median age of 36 years old that are going to live to be 82 years old. That means that, as a society, we have to account for about 1.6 billion years more of retirement than we used to. And we have six years less per person, to accumulate funds for it. I know that’s a lot of numbers and confusing math. But you can probably agree, 1.6 billion years of retirement is a big number. So it stands to reason that we’ve got to figure out how to do that. I’d love to say that the answer is to ask Americans to save more money. And if you hear people talk today, they point to some time when that happened. The problem is that history doesn’t support that option. Americans have never saved to fund the type of retirement we think of in our aspirations. When you look beyond the rhetoric here, you see that the notion of an independent, decades long retirement is something that never existed in any large scale sense in our country before the advent of social security in the 1930’s. And even after that, it existed in pockets of affluence and circumstance. But not as a whole. So the answer to this problem has to involve some function of entitlement reform or increased investment. The math is too clear for anything else. And the problem of caring for our aging population is one side of this problem. There’s another.

It is true that we now have close to double the amount of people receiving public assistance than we had in the ’50’s. But we also have almost an exactly equal population living above the poverty line that lived below it 60 years ago. That’s probably not coincidental. Which likely means you likely have to be comfortable with one out of four Americans living below the poverty line, if you are comfortable with eliminating public assistance. I am not. There are however, pockets of our society that don’t seem to be moving past the choice of poverty or public assistance. Our urban poor, which really means minority population, is disproportionately dependent on government assistance.

In 1959, 55% of African Americans lived below the poverty line. I use that population as a proxy because we had no other reliable minority data that tracked back that far. So what we’ve done, is move our urban poor out of poverty, which is good, we’d admit, and into dependence. Bear with me here because this next sentence is going to bother some people. I’ll take dependence over poverty. Which I get is a heated debate. I’m not interested in the risks that come with dumping a quarter of the population below the poverty line. Because large populations of poverty are bad. Really, really bad. And not just for those in poverty. They destabilize nations, they ruin economies they do a lot of things that I’ve witnessed first hand to make life and progress hard for countries around the globe. Massive populations in poverty are to be avoided at all costs. What we have today is better than what we had. But it’s not good enough. And it’s not sustainable. So something needs to be done. But what?

When it comes to the social safety net, we should be prepared to dynamite the whole system in the name of something that works. I’m not saying cut it out. I’m not saying make it less. I’m not saying make it more. I’m saying make it different than what it is. Because what it is does not solve is our massive segregation gap that we have between our urban, minority poor and everyone else. This will take some very “non-governmental” thinking though. But please, let’s get past the two choices that we have now. More of the same…or cut it all out so they can stand on their own two feet. We need to disrupt the status quo. And we can do that. We’re Americans and we’ve invented or perfected most of the useful things in the world today. Let’s get out of our own way politically, and aim the same passion that put us on the moon using slide rules and pencils at revolutionizing our social safety net.

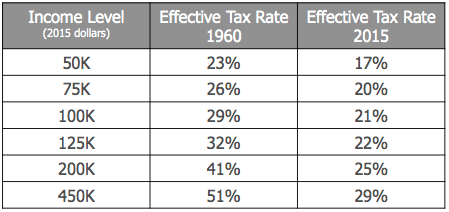

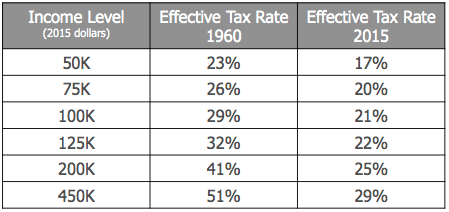

As for the retirement problem, the math behind this is extremely difficult. It’s hard to imagine how in the world we solve for this without changing it. Either our retirement age has to increase or our investment does. Or some function of both. I understand that when we say investment, that means taxes. And Americans have an allergic reaction to taxes. So much so that we’ve told ourselves, with great certainty that a dollar earned today doesn’t go as far as it used to. Which means that inflation is out of control. Or taxes are. Well, inflation isn’t, compared to wages. So it must be taxes. Actually, it turns out it’s neither. Let’s take a look at the federal income tax rates from 1960 and compare them to now, as a function of income.

Table-2. Data compiled form the Internal Revenue Service

It’s clearly, unarguably less today. When you take into consideration payroll taxes though, those things that we have to pay to fund social security and medicaid, it actually closes the gap between our 2015 and 1960 tax payments. But it still doesn’t put us in a situation where the government is taking a bigger chunk out of our paychecks then they used to. Which is why taxation falls into the “same” bucket in our comparison above. But we are asking them to pay for twice the social safety net programs than we used to and 1.6 billion years of retirement that simply didn’t exist before. So something has to change. This is one place where, from a quality of life perspective, things are much better today than they were in the good old days. But from a sustainability perspective, we’re in a heap of trouble if we stay on our current path. And trouble that is going to land squarely on my generation when it’s time to retire.

Crime

There’s more crime today as a percentage of our population than there was in the 1950’s. According to the data from the U.S. Department of Justice, you are 2.5 times more likely to be the victim of a violent crime today then you were 60 years ago. The increases in property related crimes was more slight. But oddly, the murder rate is the same. Which means we’re assaulting and raping each other a lot more than we used to. But we’re not killing each other more. There’s actually an encouraging trend here in the data though. Our violent crime rate in America hit it’s historic peak in the early 90’s. Since then we’ve seen a dramatic decrease reducing modern violent crime rates to the levels of the mid 1960’s and trending towards the previous decades. Despite the amount of high profile gun violence, we’re safer today then we’ve been in about 50 years. With twice the population living in the same amount of territory. So we should feel pretty good about it.

The issue that compares least favorably than any other issue besides children born to single parents is our incarceration rate. We have 3.5 times the percent of our population in prison today than we did in the 1950’s. And our population has nearly doubled. To put it in even clearer perspective, we have 4% of the world’s population and 25% of the worlds prison population. We have more people in prison than China and Russia combined. And it started when we started putting people in prison for drug offenses.

In 1984, President Reagan signed into law the Sentencing Reform Act as part as the Comprehensive Crime Control act that mandated sentencing minimums and consistency federally. This was a “tough on crime” bill for which two very clear data patterns followed. The first was our incarceration rate almost immediately doubled. The second, was an immediate decrease in non-violent crime and an equally steep decrease in violent crime within a decade. Mind you, one may not have caused the others but it’s important to call out data patterns because it allows us to say at least that the legislation did not make us less safe. And though it may not feel right, it does correlate to a period of decreased crime. Which tells us that massive populations of incarceration are not a crime or safety problem. They’re a societal segregation problem. Because right now, when you go to jail, you clearly aren’t likely to commit a crime against society while you’re in jail. But you and your family have opted out of most of the American dream going forward. Which is a problem for the last section. Our social safety net. I’m not sure the data supports reducing sentencing limits or legalizing drugs from a safety perspective. But it does tell us we have way too many people in jail, and it’s contributing to the segregation of our country.

Global Stability

We can solve this one pretty quickly. The first half of the 20th century was the most dangerous time in the history of mankind. The second half, continuing on into the early 21st century has been the most peaceful. Though the second half of the 50’s was free from war, we were about a decade removed from WWII and a few years removed from the Korean War. During those two wars, we lost just under a half a million Americans. The world lost 60 million people. Including the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the 14 years of war that about 1% of Americans contributed in, and we’ve lost a little over 10,000 people to combat. We’re not without conflict. But no matter how it feels, the world is safer. And it’s not close.

So What

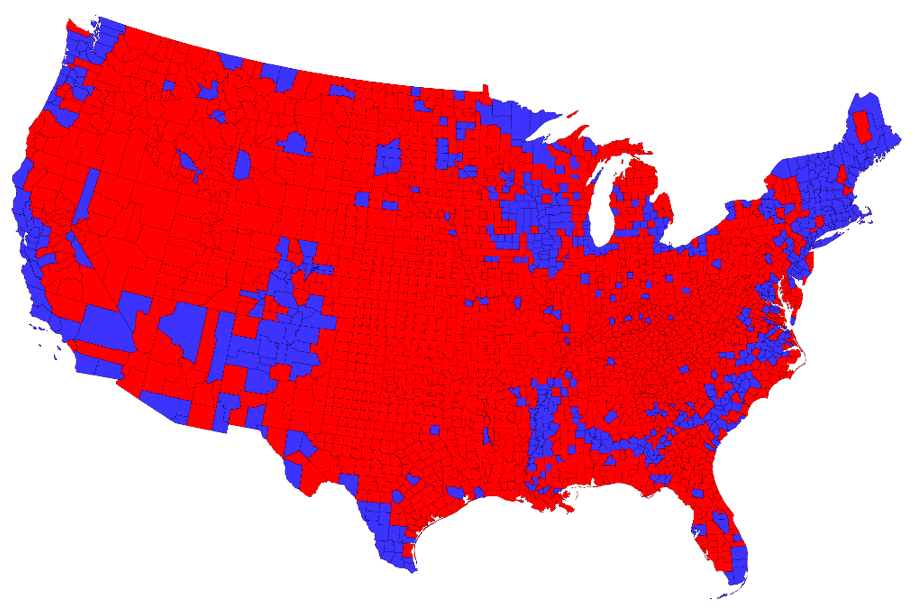

There’s a lot of metrics that you could track down and a lot more that you could add to try to make a point one way or another. But the bottom line is this. Things were different in the “golden age” of American than they are today. In some ways they were better. But in more ways they were either worse or simply different. Right now there is a large part of the American public, our media and our overall consciousness that believes that we’ve wandered off of a path to greatness and that we are far worse off today then we were then. And that we need to return to “better times.” I would issue a word of caution for those that hold that sentiment. Both the data and the historical context are clear. For a very narrow portion of our society, healthy white men, things were better. If by better you meant you had no competition for work in an economy that was booming because of the impossible to duplicate post WWII reconstruction. For everyone else, things weren’t better. They were far, far worse. I’ll play this out in a real world experience, mine.

I’m a pushing 40 white man with a graduate degree. By all rights, I should look back at the 1950’s as a time that would have suited me fine. But a closer look tells you different. My wife, half Latina, would have faced some level of segregation in primary and secondary school for her ethnicity. Even if she made it past it and completed the two graduate degrees she has today, she would have no place helping homeless veterans as she does now, other than administrative support in the mental health profession. My mother’s four year battle with ALS that rendered her incapacitated for the last three, would have bankrupted my entire family. My non-verbal, autistic child would be locked away in an asylum, the doctor’s would be recommending a lobotomy as his best path for treatment. When I returned from war and struggled with anxiety and depression, I would have turned to the bottle and soldiered on in silence. This is would have been my reality. And I’m a healthy white man. Which means I’m in the best shape out of any one. If I were black, I would be in poverty and not allowed to eat or attend school with white people in most states. If I were gay, I would be a pervert. If I were handicapped, I had no path to independence or contribution in society. This was the reality. It was cruel and unforgiving. And it makes for a bad bumper sticker.

As for the next generation, they’re fine. They’re more educated and more technical than ever before. And we’re right. They wouldn’t last a minute on the assembly line in a plant. Which is good. Because we don’t have many of those these days. Which is fine. Because we’ve adapted to our role at the top of the global economic food chain as a services and consumption economy. That’s how it works. But they wouldn’t last a minute 60 years ago. Just like their parents wouldn’t have lasted a minute in the coal mines and blast furnace of the generation before. Just like that generation never would have lasted a minute scratching out a living off the land in an agricultural society. Just like that generation of farmers wouldn’t have lasted a minute blazing a trail from sea to shining sea. Just like that generation never would have had the guile to throw off an unjust government.

That’s how this thing works. One generation judges the next on their ability to exist in the past. And that generation learns the skills it needs to survive for the next fifty years. And doesn’t learn the ones it took to survive in the last. But they’re fine. The kids I served with in war and now show up at my door in the big time technology industry can do things I can’t. What I know, would not have gotten me hired at 22 today. But instead of being scared of that, I learn what I can from them and help bridge the gap between what I know and have experienced and what they do so that we might walk across it to a collectively brighter future. It’s called mentoring. And when you do it, they listen. And when you whine about “kids these days” they don’t. So give it a rest. You sound old and scared.

So what does it all mean? Well, as far as the political discourse it means this. If you’re a progressive elected official, you can stand back and admire the social progress that you’ve help engineer over these last 60 years that has made life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness more attainable for more groups of people. But there’s one thing that you can’t say and it’s that the social safety net that we have in place is moving people out of poverty and into financial stability. It’s not working. And you need to own that and help drive solutions in an economy where urban middle class jobs do not exist any more.

If you’re a conservative, you can congratulate yourself that we’ve managed to shoulder the massive load of providing government and services for 320 million people without taxing our constituents to death or crippling capitalism. But what you haven’t done is find a way to do that without deficit spending. And when you’re realistic about our aging, longer living population, you need to own doing something about our current revenue gap, or when my generation retires, the draw we will have on the broader economy will cripple us. It’s simple math. And please stop with the “let’s go back to Mayberry” rhetoric. Because it’s not real. And for most of us we just hear thinly veiled bigotry and close minded thinking. It’s not helpful.

For those of us who still suffer from the burden of free will with our votes, let’s keep an ear out for anything that starts to resemble that kind of discussion. Until then, just keep tuning out the fear-mongering or blind compassion. It’s not worth the mind space. We’ve got real things to solve. And getting back to the “good old days” doesn’t solve any of it.

Table-1. Data compiled form the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Labor, U.S. Census Bureau, The Pewe Research Center, The Brookings Institute and Gallup

Table-1. Data compiled form the U.S. Department of Justice, Department of Labor, U.S. Census Bureau, The Pewe Research Center, The Brookings Institute and Gallup